As the intricate ecosystems around us face unprecedented stress—from antibiotic overuse to climate change—an often overlooked yet vital layer of biodiversity is under threat: microbial life. Bacteria, fungi, and other microbes play foundational roles in human health, agriculture, and environmental resilience. Recognizing their critical importance, scientists are now creating dedicated microbial biobanks—“ark-like” repositories preserving microbial diversity for future scientific, medical, and ecological applications.

Why Microbial Biobanking Matters

Preserving Microbial Diversity

Just as seed banks conserve plant species, microbial biobanks safeguard microbes that may vanish due to industrialization and environmental shifts. The Microbiota Vault, based in Switzerland, has initiated a global effort to preserve gut microbiome samples before they disappear. Additionally, human fecal biobanking projects aim to freeze 10,000 stool samples by 2029, recognizing microbial loss as a public health concern .

Enabling Precision Medicine

Microbial diversity has direct implications for health. The Mayo Clinic’s stool biobank, housing over 2,000 samples, is used to personalize cancer therapies based on gut microbiota profiles. Such initiatives illustrate how microbial biobanks support diagnostics, targeted treatments, and microbiome restoration therapies.

Powering Environmental and Industrial Innovation

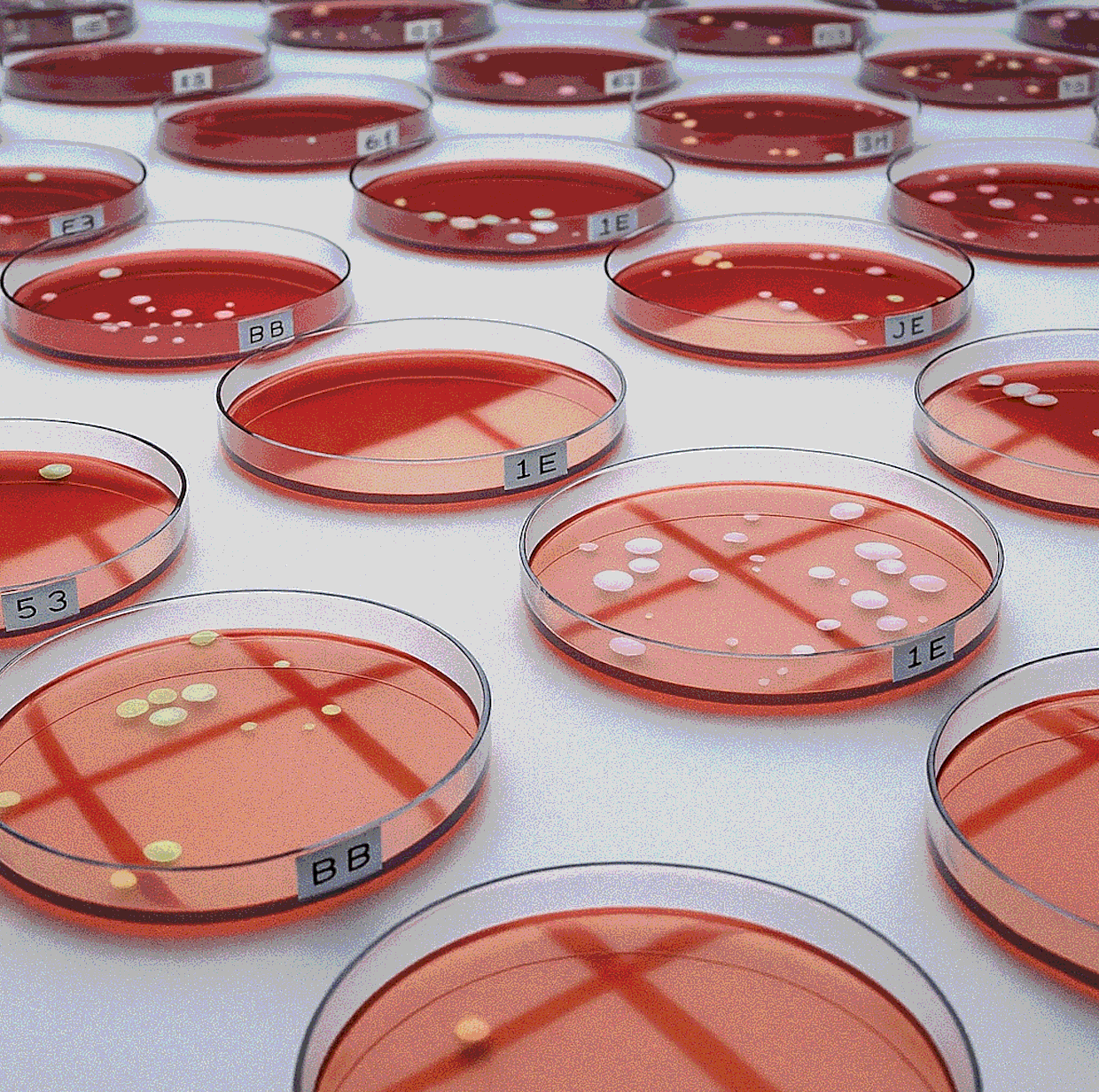

Catalogued microbial strains—like those stored at JMRC in Germany—are invaluable for discovering enzymes, bioactive compounds, and biodegradation tools . Metagenomic biobanks also provide genetic blueprints for microbes that cannot be cultured in labs, expanding possibilities in biotechnology and conservation.

Examples of Microbial Biobank Initiatives

● Microbiota Vault (Switzerland): Archiving diverse gut microbiomes from global communities to counteract microbial erosion .

● Swiss “poop vault”: Aiming to preserve 10,000 human stool samples by 2029 for future microbiome restoration .

● Mayo Clinic stool biobank: Over 2,000 samples used to tailor cancer treatments via microbiome analysis .

● Jena Microbial Resource Collection (Germany): Holding thousands of live bacterial and fungal isolates for research and natural product screening .

Scaling Infrastructure and Technology

During its initial “launch phase”, the Microbiota Vault collected over 1,200 human fecal specimens and nearly 200 fermented food samples from seven countries, establishing standard protocols for sample handling, cryostorage, metadata annotation (using MIxS standards), and remote sequencing . This laid the groundwork for expansion into a permanent, multi-site global network.

Ethical, Legal and Social Dimensions

Beyond the science, microbial biobanking raises critical ethical and legal issues. Ensuring informed consent, addressing biosecurity risks, and navigating benefit-sharing agreements under frameworks like the Nagoya Protocol are essential for responsible stewardship. Equitable collaboration with indigenous and rural communities reinforces trust and promotes biodiversity conservation .

Multifaceted Applications Ahead

Looking beyond medicine and ecology, microbial biobanks are accelerating innovation in areas ranging from sustainable agriculture and food fermentation to cosmetics and even space exploration. Shared repositories of microbial strains drive applications like next-generation probiotics, soil microbiome enhancements, enzyme-based bioremediation, and life-support systems for long-term space missions.

Looking Ahead

Microbial biobanks are poised to become central to the future of medicine, ecology, and biotech innovation. As microbial ecosystems face pressure and vanish, repositories like microbial “arks” will equip scientists with the diversity they need to:

● Restore healthy human microbiomes

● Develop next-generation antibiotics and probiotics

● Engineer enzymes for sustainable agriculture

● Decode environmental resilience to climate change